Introduction

For many, making the journey from a student or intermediate suit into a larger, more advanced wingsuit safely can present a number of challenges. The biggest of these is managing the extra wing size and the additional forward speed (with the resulting higher internal pressures).

This extra pressure makes closing the suit down much trickier. To get it right, we have to rely on a technique called flaring to manage our forward speeds and internal pressure—and, in so doing, to enjoy a clean deployment sequence.

Make no mistake: flaring that suit effectively is an essential skill. If you struggle—even a little bit—to flare a wingsuit, your progression into bigger, faster wingsuits is likely to be a bruising ride.

With that said, you couldn’t be faulted for finding it a little tricky. There’s a lot of inconsistency in the way it’s taught. Case in point: somehow, I still see jumpers using their knees as a means to slow a suit down just enough to execute a deployment. I also see an alarming number of jumpers moving from intermediate to larger suits who have not learned—let alone practised—the flare before moving into these suits. The reason they usually give is that practising the flare in a “little suit” is pointless.

While it’s true that the bigger classifications of wingsuits can create bigger, more visually pleasing flares (due to the higher energy and speeds they can generate), any wingsuit of any size can give you a good functional flare. Besides, you’d better make good use of the margin for error that comes standard with a “little suit:” the smaller the suit, the less likely it is that your jump will end in a twisty, expensive deployment.

Flare-averse? Crossing your fingers? Eyes on a bigger, faster suit? This article has been written for you. I’m here to demystify the wingsuit flare, and to provide my best guidance on a consistent way to execute it.

Why flare a Wingsuit?

Let’s start here: why bother?

There are three main uses for a flare in a wingsuit. These are, in ascending order of use:

- In wingsuit BASE jumping, to gain vertical separation from an object—typically a bit of terrain—before deploying.

- To ‘clip’ the top of a competition window when competing in a Wingsuit Performance competition.

- To reduce internal wingsuit pressure and forward speed, with the intention to keep the suit flying for longer during a canopy deployment sequence. When we flare, we aim to put ourselves into a more head-high attitude, thereby slowing down our wingsuit—while still keeping control—and making deployment cleaner and easier.

Perhaps obviously, it’s the last use case we will be focusing on today: the skill of using the flare as a means to complete a super-nice deployment.

Anatomy of a Wonky Flare

The standard wingsuit “shutdown” technique—taught during every WS1, in which we close the arm and leg wings down pre-deployment—serves a jumper very well in small and intermediate wingsuits. Bigger, faster suits, however, generate pressure in the arm- and leg wings during normal flight that might be more than most people can manage to shut down. It follows that we need to find a different way to slow the suit down that reduces the internal pressure of the suit.

As with most things in life, there are good ways and bad ways to achieve this. An unfortunate number of pilots have devised ways of “air braking” their suit by dropping the knees into the airflow like this:

While this technique will slow you down, it does so at the cost of control. Why? Because dropping the knees removes airflow over the top of the wings, effectively stopping the suit from flying—and thus introducing instability when going for the pull. This instability can then cause uneven deployments, induce line twists and incur other unwanted side effects that could escalate further as the canopy deploys.

Let’s set that old chestnut aside, then, and learn the right way to flare.

What you will need:

- Any wingsuit—the smaller, the better. (These skills will always be of benefit and, in the long run, will make you feel way more comfortable as you progress towards more and more advanced suits.)

- The skills of effectively shutting down your wingsuit, WS1-style, and recovering from an unstable position. (If you hold the flare too long—which you likely will, when you’re learning—you risk stalling the suit and will need to cope with the instability that results.)

- A personal data logger, such as a Flysight. I myself also use the free Skyderby tool to analyse my own and my students’ Flysight data. Using Skyderby, we can clearly see the effectiveness of any given flare.

- Lots of altitude. When trying this for the first few times—as with all of your skill experiments in skydiving—it is highly advised to practise at a high, safe altitude until you achieve mastery.

- A practised eye to watch your back. It is always recommended to have a chat with your local Wingsuit Instructor before trying new techniques for the first time. Connect with a coach.

Three Steps to Flare

Remember when you learned to flare your canopy? You were probably taught to break it into phases, which you then knitted together over time into a single, smooth action. That’s how the wingsuit flare works as well.

Step 1: Add Speed

All manoeuvres in a wingsuit—changing altitude, transitions, etc.—have an associated energy cost . Typically, this tends to be the speed at which we fly. If we attempt to flare with a forward speed that’s too low, we’ll stall…and, in doing so, cause ourselves an armful of problems. Stage one, then, is to make sure we have enough energy—speed—in the wingsuit before we go for the flare.

As a starting point, let’s assume we’re flying in a neutral, palms-up body position, which should look similar to this:

To quickly add speed, we need to relax the shoulders. This will allow the wing sweep to come back a little bit. In doing so, we’re still ensuring the wings are fully engaged, but we’re reducing the pressure we are exerting on the wings.

At the same time, we also want to roll the suit into a head-low orientation and remove any arching of the back.

Finally, we need to drop the head by bringing our chin closer to our chest. This allows the tail to drive the suit down.

Once all these actions are in place, the body will be in a position that looks more-or-less like this, the speed-generation position:

Step 2: Roll into the flare

Once we’ve held the head-low speed-generation position to allow the energy to build up, we’re ready to start the next phase: rolling into the flare.

To begin, we need to get the maximum performance we can from the wings. To achieve this, we need to bring our arms up and forward in line with the head/body, mimicking the shape of the letter T by pushing our arms into the leading edge of our wings

In practice, a true T-shape can’t really be done. The design of the suit—specifically, where the wings connect near the feet—will prevent the arms from coming into alignment with the shoulders. With that said, the act of trying to create a “T” with the body will tighten the arm wings and generate a huge amount of power, and that power is the goal.

The result (in terms of arm position, that is; we are not trying to stand on our tail) would look something like this:

When executed correctly, this body position will cause the suit to fly “up,” exerting palpable pressure on the shoulders and arms, as we now “consuming” far more air than before.

To further support the flare, we need to make sure we:

- Engage the tail wing (by keeping our legs as wide as the suit allows)

- Point the toes (to stretch the suit firmly along the length of our body)

Fluidly moving through that “roll” will put the body into a head-high orientation. The resulting body position—the flare—should look something like this:

Jumpers often move far too quickly into this final position, as if yanking a control stick back in a single violent movement. As with a canopy flare, moving from a position of speed into a flare should takes 3-5 seconds and must be done smoothly; gradually.

If we do “pull the stick back too quickly,” we can expect to lose a critical amount of speed and exert lots of unnecessary stress on the suit (and our bodies!) with the resultantly violent head-high position. Let’s aim to avoid that.

Step 3 – Hold, hold, hold

With the start of the flare, the suit has now massively increased its glide ratio. Our task is to now hold this position and allow the suit to fly until it’s time to deploy our main parachute. The amount of time this takes will vary based on how much speed has been introduced in the first step and how cleanly the flare “roll” is executed during stage two.

Predictably, the longer we hold the flare, the slower the suit will get—and the closer it will get to its stall point, a dynamic which introduces its own challenges. Equally: if we try to deploy too early, then it’s likely we haven’t sufficiently slowed our flight. In that case, we may struggle to fully collapse the suit—or we’ll end up introducing the main into too much airflow and cause an off-heading or snappy opening*. You will need to experiment with your timings to find the “sweet spot” for your suit and flying style.

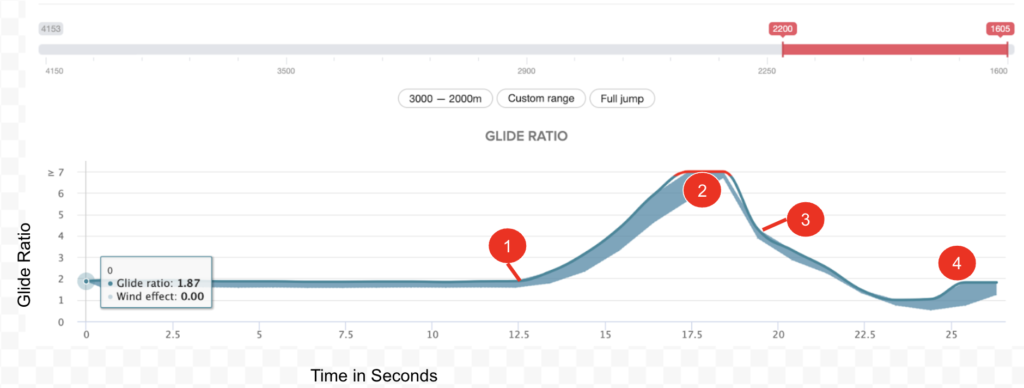

The below is a track of my own, shared from Skyderby. It shows the closing points of the jump— my transition into the flare and subsequent canopy deployment—while flying a Phoenix Fly Strix.

- At Point 1, I am starting my flare at 12.5 seconds (into the selected track data). I hold this flare position for nearly five seconds. As I do, I increase my glide ratio from 1.88 to near 7.17.

- At Point 2, I have held the flare for an amount of time past which I feel that I cannot get any more flare out of the suit, so I begin my “shutdown” (which drops the glide ratio back down to 4).

- Notice the little kink in the chart at Point 3. This marks the time I deploy my main canopy: thanks to the flare, into a much slower relative wind that prolongs the opening sequence and allows for a much nicer opening (and ease of access to the BOC).

- At Point 4, the canopy is now fully inflated. I am now in a position to sort out the wingsuit and begin my journey back to the dropzone.

Troubleshooting

Several problems tend to plague jumpers when learning to flare. With the caveat that you should check with your local wingsuit coach and always remain altitude aware, here are some basic recommendations..

Whoops! I stalled!

When this happens, you’ll likely drop into a head-low body position and roll over your dominant side. Don’t panic—just allow the suit to roll into a head-low position and, from there, adopt the speed generation position to allow airflow to resume over the top of the suit. Recover a normal flying position and then do a quick altitude check before trying again (or going for a normal deployment).

I am too slow and now my parachute is not working!

It’s very likely you’ve deployed your pilot chute into the burble. It’s hanging out back there, waiting for some clean air to continue on its journey. Now, your job is to help it by remaining in the shutdown position and rolling your shoulders left and right a few times. This will move the burble relative to your body position. That wiggle should clear the pilot chute.

If that doesn’t work, the next thing to try is putting your chin on your chest and dropping into a head-low body position. This is another method to allow airflow back over the back of the suit to clear the pilot chute and deploy your main. A word of warning, though: if you end up going this route, you will likely have a more positive deployment than usual.

If the above two do not manage to extract your main, start thinking about your emergency procedures.

Ouch! I deployed too soon and carried too much speed.

This is very common and—when it happens—you’ll probably end up with an off-heading deployment as the canopy struggles to open in stages. It’ll pick a direction and shoot off that way quite quickly, often leading to line twists (that can be resolved in the usual way). To avoid it, simply adjust your timing during the “hold” phase.

Um…I deployed too late and now I’m waiting through a very long deployment sequence.

This is a little rarer than the former, but still common. When it happens, the canopy is struggling to open due to the lack of airflow. The only fix is to wait for it to open; as always, count for five seconds and, if that recalcitrant nylon is still struggling, it’s time to think about emergency procedures—just like a normal jump.

Practice, Practice, Practice

To this day, I still get the odd flare wrong. It might be that I’ve deployed too early and earned myself an 180° off-heading—or too late, resulting in an extra-long deployment sequence. The precise timing of a flare is damnably multi-factorial, based not just on your suit design and your flying but on wind conditions (tail or head winds), micro-positions of your hands and feet, your helmet—maybe even your mood, and the position of the stars.

Don’t let the great mysteries get you down. As a rule, if you experiment with this sequence a number of times and gradually introduce it into your wingsuit flights, you will become more adept at it. You will get more consistent results and much better, far-lower-stress openings.

The UK has a collection of excellent, passionate Wingsuit Coaches who will be delighted to teach you these techniques in person. Please feel free to reach out to any of us. We’re here to help you.